Table of Contents

1. Background and purpose of this guidance

This local practice guide has been developed to raise awareness about FGM in Peterborough and Cambridgeshire amongst practitioners. It attempts to summarise the issues for identifying, responding and preventing FGM for both children and adults. These are practice guidelines and are designed to be educative and provide advice; they are not a substitute for existing statutory guidance such as Working Together to Safeguard Children (2018)

2. What we know about FGM

What is FGM?

FGM includes any mutilation of a female’s genitals, including the partial or total removal of the external genitalia for perceived cultural or other non-medical reasons. The practice is medically unnecessary, extremely painful and has serious health consequences, both at the time when the mutilation is carried out and in later life. It was made illegal in the UK in 1985; the most recent laws covering this area is the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 and amendments within the Serious Crime Act 2015.

Who is at risk?

It has been estimated that approximately 60,000 girls aged 0-14 were born in England and Wales to mothers who had undergone FGM. Approximately 103,000 women aged 15-49 and approximately 24,000 women aged 50 and over who have migrated to England and Wales are living with the consequences of FGM.[1]

FGM can be practised at any age. People from some communities within certain countries are more likely to practise FGM than others; this does not mean that every community from a particular country does practise FGM.

Girls may be at increased risk of harm if their mother, or any sisters / female members of the extended family, have experienced FGM. FGM is practised by families for a variety of complex reasons but usually in the belief that it is beneficial for the girl or woman. However, it is illegal to:

- perform, or arrange for someone to perform, FGM in the UK (regardless of the nationality or immigration status or the perpetrator(s) or victim)

- perform, or arrange for someone to perform, FGM abroad (when either the perpetrator or victim is a UK national/permanent resident)

- encourage or assist a girl who is a UK national to carry out FGM on themselves, anywhere.

FGM is a form of child abuse and a recognised strand of violence against women and girls. It can have severe short-term and long-term physical and psychological consequences for the individual. There are a number of challenges in building a local picture of FGM in Peterborough and Cambridgeshire; we are working to establish how many cases are identified by practitioners, what proportion of FGM takes place in the UK compared to abroad and if FGM is actively practised across the County.

3. Identifying girls and women at risk

Specific factors that may heighten a girl’s or woman’s risk of being affected by FGM

There are a number of factors in addition to a girl’s or woman’s community that could increase the risk that she will be subjected to FGM:

- The position of the family and the level of integration within UK society – it is believed that communities less integrated into British society are more likely to carry out FGM.

- Any girl born to a woman who has been subjected to FGM must be considered to be at risk, as must other female children in the extended family.

- Any girl who has a sister who has already undergone FGM must be considered to be at risk, as must other female children in the extended family.

- Any girl withdrawn from Personal, Social and Health Education or Personal and Social Education may be at risk as a result of her parents wishing to keep her uninformed about her body and rights

Indications that FGM may be about to take place soon

The age at which girls undergo FGM varies enormously according to the community. The procedure may be carried out when the girl is new born, during childhood or adolescence, at marriage or during the first pregnancy. However, the majority of cases of FGM are thought to take place between the ages of 5 and 8 and therefore girls within that age bracket are at a higher risk.

It is believed that FGM happens to British girls in the UK as well as overseas (often in the family’s country of origin). Girls of school age who are subjected to FGM overseas are thought to be taken abroad at the start of the school holidays, particularly in the summer holidays, in order for there to be sufficient time for her to recover before returning to her studies.

There can also be clearer signs when FGM is imminent:

- It may be possible that families will practise FGM in the UK when a female family elder is around, particularly when she is visiting from a country of origin.

- A professional may hear reference to FGM in conversation, for example a girl may tell other children about it.

- A girl may confide that she is to have a ‘special procedure’ or to attend a special occasion to ‘become a woman’.

- A girl may request help from a teacher or another adult if she is aware or suspects that she is at immediate risk.

- Parents state that they or a relative will take the child out of the country for a prolonged period.

- A girl may talk about a long holiday to her country of origin or another country where the practice is prevalent.

Indications that FGM may have already taken place

There are a number of indications that a girl or woman has already been subjected to FGM:

- A girl or woman may have difficulty walking, sitting or standing.

- A girl or woman may spend longer than normal in the bathroom or toilet due to difficulties urinating.

- A girl may spend long periods of time away from a classroom during the day with bladder or menstrual problems

- A girl or woman may have frequent urinary or menstrual problems.

- There may be prolonged or repeated absences from school or college.

- A prolonged absence from school or college with noticeable behaviour changes (e.g. withdrawal or depression) on the girl’s return could be an indication that a girl has recently undergone FGM.

- A girl or woman may be particularly reluctant to undergo normal medical examinations.

- A girl or woman may confide in a professional.

- A girl or woman may ask for help, but may not be explicit about the problem due to embarrassment or fear.

4. The need to safeguard girls and young women at risk of FGM

Under section 47 of the Children Act 1989, anyone who has information that a child is potentially or actually at risk of significant harm is required to inform social care or the police. A local authority should exercise its powers to make enquiries to safeguard a girl’s welfare under section 47 of the Children Act 1989 if it has reason to believe that a girl is likely to be subjected to or has been subjected to FGM. However, despite the very severe health consequences, parents and others who have FGM performed on their daughters do not intend it as an act of abuse – they believe that it is in the girl’s best interests to conform with their prevailing custom. Therefore, where a girl has been identified as being at risk of significant harm, it may not always be appropriate to remove the child from an otherwise loving family environment. Where a girl appears to be in immediate danger of FGM, consideration should be given to legal interventions.

Section 70-75 of the Serious Crime Act 2015 extended the scope of extra territorial offences, granted victims of FGM life- long anonymity and introduced a new offence of failing to protect a girl from the risk of FGM. These provisions introduced FGM Protection Orders and a mandatory duty for front line professionals to report FGM.

Talking about FGM

FGM is a complex and sensitive issue that requires professionals to approach the subject carefully. When talking about FGM, professionals should:

- ensure that a female professional is available to speak to if the girl or woman would prefer this;

- make no assumptions;

- give the individual time to talk and be willing to listen;

- create an opportunity for the individual to disclose, seeing the individual on their own in private;

- be sensitive to the intimate nature of the subject;

- be sensitive to the fact that the individual may be loyal to their parents;

- be non-judgemental (pointing out the illegality and health risks of the practice, but not blaming the girl or woman);

- get accurate information about the urgency of the situation if the individual is at risk of being subjected to the procedure;

- take detailed notes;

- use simple language and ask straightforward questions;

- use terminology that the individual will understand, e.g. the individual is unlikely to view the procedure as ‘abusive’;

- avoid loaded or offensive terminology such as ‘mutilation’

- use value-neutral terms understandable to the woman, such as:

- “Have you been closed?”

- “Were you circumcised?”

- “Have you been cut down there?”

- be direct, as indirect questions can be confusing and may only serve to reveal any underlying embarrassment or discomfort that you or the patient may have. If any confusion remains, ask leading questions such as:

- “Do you experience any pains or difficulties during intercourse?” ( as appropriate)

- “Do you have any problems passing urine?”

- “How long does it take to pass urine?”

- give the message that the individual can come back to you if they wish;

- give a clear explanation that FGM is illegal and that the law can be used to help the family avoid FGM if/when they have daughters.

An accredited female interpreter may be required. Any interpreter should not be a family member, not be known to the individual, and not be an individual with influence in the individual’s community. This is because girls or women may feel embarrassed to discuss sensitive issues in front of such people and there is a risk that personal information may be passed on to others in their community and place them in danger.

5. Individual agency responsibilities

FGM is not a matter that can be left to be decided by personal preference or tradition, it is an extremely harmful practice. FGM is child abuse, a form of violence against women and girls, and is against the law with a maximum of prison sentence of 14 years. All professionals should be familiar with the risks indicators of FGM and be aware of what steps to take if they are concerned that a child/ young person has or is likely to be the victim of FGM. Remember reporting FGM is a mandatory legal duty.

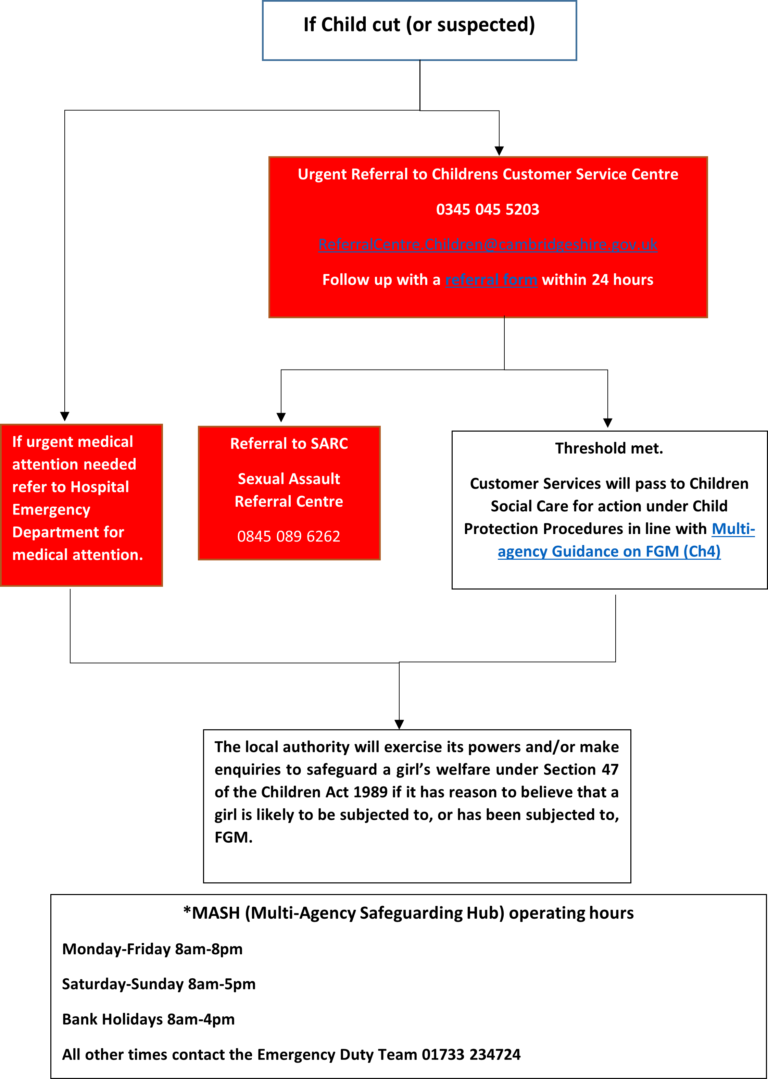

A flow diagram (Diagram 1) explaining the pathway to follow if you think a child/ young person has or is likely to be cut can be found at Appendix 1.

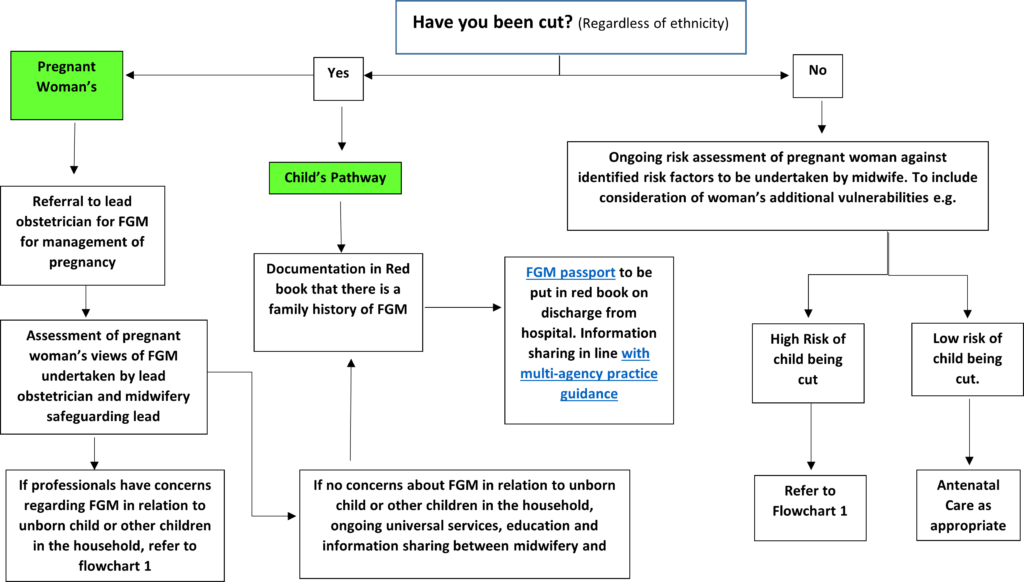

A flow diagram (Diagram 2) describing the pathway for the management of an unborn child and mother can be found at Appendix 2.

Further details regarding specific guidelines can be found in HM Government Multi Agency Practice Guidelines: Female Genital Mutilation (2016);

- Health Professionals (Chapter 6)

- Police Officers (Chapter 7)

- Children’s Social Care (Chapter 8)

- School, Colleges and Universities (Chapter 9)

Appendix 1 – You Suspect a Child or Young Person has undergone FGM Flowchart

Appendix 2 – FGM Pathway Management for Pregnant Women Flowchart

[1] HM Government – Multi Agency Practice Guidelines: Female Genital Mutilation (2016)

Guidance updated July 2019