Revisions

Version | Page & Paragraph | Amendment | Date |

June 2025 | Completion of review and amendments made to document | 20.6.25 | |

September 2025 | Page 6 | Definition of hoarding | 17.9.25 |

September 2025 | Launch of document | 17.9.25 | |

October 2025 | Page 20 | Addition of protective characteristics | 15.10.25 |

Table of Contents

MARM Priniciples

Introduction

This document describes guidance for conducting Multi-agency Risk Management (MARM) and should be read alongside the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Multi-Agency Adult Safeguarding Procedures.

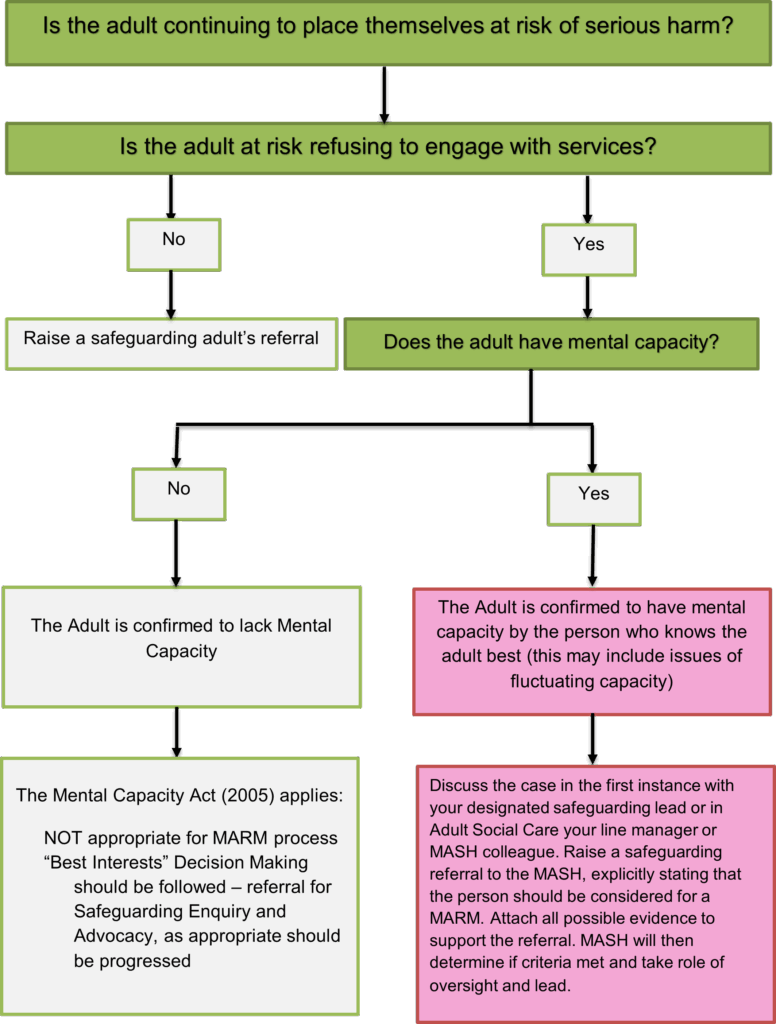

The Multi-Agency Risk Management (MARM) process provides professionals from all agencies with a framework to facilitate effective multi-agency working with adults (aged 18+) with care and support needs and at risk of harm who are deemed to have mental capacity for specific decisions that may result in serious harm/death through severe self-neglect or risk-taking behaviours and refuses or is unable to engage with services.

Note: If the risk(s) is not at a level which may lead to serious harm or death the MARM process does not apply and should not be followed. Where the adult lacks capacity the Mental Capacity Act (2005) the MARM should not be employed and action should be taken under Best Interests (See the MARM Principles on Page 3). |

The guidance should be used flexibly and in a way that achieves best outcomes for the adult. It does not, for example, specify which professionals need to be involved in the process, or prescribe any specific actions that may need to be taken as this will be decided on a “case by case” basis through coordinated multi-agency working; in line with the Making Safeguarding Personal (MSP) Principles, agreed information sharing protocols, the Data Protection Act 2018 (the UK’s version of the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) 2018), and in full compliance with the Articles and Protocols of the Human Rights Act (1998) and other applicable legislation. More information resources about the Human Rights Act (1998) can be found at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/human-rights/human-rights-act

It should be noted that any professional and/or agency/organisation can decide that a MARM referral should be made.

Establishing Mental Capacity

A person must be assumed to have mental capacity unless it is established that on the balance of probability that they lack capacity. Capacity will be determined in line with the requirements of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. Where someone lacks ‘mental capacity’, anything done for or on their behalf must be in their ‘best interests’. Where this happens, practitioners should refer to guidance on best practice in dealing with decision-making and incapacity[1], and on the principle of “best interests” of the person who lacks capacity. There may be instances where a working assumption of capacity is made but it may need some further clarification. This can be explored on an ongoing basis once the MARM is commenced. “Whilst the assumption of capacity is a foundational principle, professionals should not hide behind it to avoid responsibility for a vulnerable individual. In some situations, where the risk to the individual is high, where there is potentially legitimate doubt as to the persons capacity or good cause for concern for thinking that the person may lack capacity to take a relevant decision, the more professionals should document clearly the risks that have been discussed with the person and the reasons why it is considered that the person is able and willing to take those risks. In many situations this evidence should be recorded in a capacity assessment even if the conclusions reached are the person is none the less able to make their own decision.”

An individual who has the mental capacity to make a decision and chooses voluntarily to live with a level of risk, is entitled to do so, although where the level of risk is very high, practitioner and managers must consider whether the Inherent Jurisdiction of the Court may apply. The law will treat that person as having consented to the risk and so there will be no breach of the duty of care by professionals or public authorities. Robust recording of considerations and decisions is critical in evidencing defensible decision-making.

Legal advice should always be sought when Inherent Jurisdiction[2] may be a factor.

Definition of Adult at Risk

According to the Care Act (2014), an adult at risk is a person who:

- Has needs for care and support (whether or not the local authority is meeting any of those needs) and

- Is experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect, and

- As a result of those care and support needs is unable to protect themselves from either the risk of, or the experience of, abuse or neglect.

Definition of Serious Harm

For the purpose of this policy, “serious harm” refers to the death or injury (either physical or psychological) which is life threatening and/or traumatic and which is viewed to be imminent or very likely to occur.

Definition of Self-Neglect

The Social Care Institute of Excellence (SCIE) defines self-neglect as having three possible strands:

- Self-care – lack of care over personal hygiene, health, nutrition or hydration leading to potentially severe harm or death.

- Environment – lack of care leading to squalor or hoarding.

- Refusal of services which may mitigate harm – such as help with alcoholism, or risk-taking behaviour.

The Care Act (2014) includes self-neglect within adult safeguarding and some self-neglect cases will be managed through the safeguarding procedures under a Section 42 enquiry. However, not every case of self-neglect will meet the criteria for a safeguarding enquiry. The critical factor is likely to be if an adult is able to manage their own behaviour to prevent harm to themselves.

An example of this may be where the adult refuses to engage with care/support services and evidence suggests that the “friendships” they are keeping, or their social network are placing them at risk of serious exploitation, harm or death. Examples of this type of situation can include the exploitation of adults in situations of sexual abuse, sex trafficking, modern slavery and cuckooing (the practice of taking over the home of a vulnerable person in order to establish a base for illegal drug dealing, typically as part of a county lines operation).

Definition of Hoarding

Hoarding is the excessive collection and storing of items, often in a chaotic manner, to the point where their living space is not able to be used for its intended purpose.

Hoarding is considered a significant problem if:

- the amount of clutter interferes with everyday living – for example, the person is unable to use their kitchen or bathroom and cannot access rooms

- the clutter is causing significant distress or negatively affecting the quality of life of the person or their family

A person with a hoarding disorder may have significant difficulty in discarding or parting with possessions. They may experience distress at the thought of getting rid of items or simply be unable, either physically or through other health-related factors, to get rid of things despite acknowledging that changes need to be made. The items can be of little or no financial value.

Hoarding is considered a standalone mental health disorder, however, it can also be a symptom of other medical disorders. It is not a lifestyle choice and hoarding must always be treated as a sign of vulnerability.

For cases of Self-Neglect and Hoarding please follow the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Adults Partnership Board’s

- Multi-Agency Policy and Procedures to Support People who Self-Neglect – Multi-Agency Policy and Procedures to Support People who Self-Neglect | Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Partnership Board (safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk)

- Multi-agency Protocol for Working with People with Hoarding Behaviours – Multi-agency Protocol for Working with People with Hoarding Behaviours | Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Partnership Board (safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk)

Case scenarios where the MARM Guidance may apply are included in Appendix A.

Making Safeguarding Personal and the Lived Experience of the Adult

Making Safeguarding Personal requires practitioners to find out about the lived experience of the adult.

As worded in the Care and Support Statutory Guidance (14.5):

Making safeguarding personal means it should be person-led and outcome-focused. It engages the person in a conversation about how best to respond to their safeguarding situation in a way that enhances involvement, choice and control as well as improving quality of life, wellbeing and safety.

Making Safeguarding Personal is about having conversations with people and is about seeing people as experts in their own lives whilst working alongside them.

Professionals should work with the adult at risk to establish what being safe means to them and how that can be best achieved. Professionals and other staff should not be advocating “safety” measures that do not take account of individual well-being, as defined in Section 1 of the Care Act 2014. It is important to listen to the adult at risk both in terms of the alleged abuse and in terms of what resolution they want. However, professionals should be mindful of what is achievable and realistic as an outcome for the adult at risk and be able to explain what can be done to support to the adult at risk. Individuals have a right to privacy; to be treated with dignity and to be enabled to live an independent life.

The focus of the adult safeguarding procedure is on achieving an outcome which supports or offers the person the opportunity to develop or to maintain a private life. This includes the wishes of the adult at risk to establish, develop or continue a relationship and their right to make an informed choice. Practice should involve seeking the person’s desired outcomes at the outset and throughout the safeguarding arrangements and checking whether those desired outcomes have changed or have been achieved.

Intervention should be proportionate to the harm caused, or the possibility of future harm. As well as thinking about an individual’s physical safety it is necessary to also consider the outcomes they want to see and take into account their overall happiness and wellbeing.

Assessments of risk should be undertaken in partnership with the person, who should be supported to weigh up risks against possible solutions. People need to be able to decide for themselves where the balance lies in their own life, between living with an identified risk and the impact of any Safeguarding Plan on their independence and/or lifestyle.

Further information and resources for Making Safeguarding personal and the Lived Experience of the Adult can be found at:

- https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/our-improvement-offer/care-and-health-improvement/making-safeguarding-personal

- https://www.local.gov.uk/msp-toolkit

- Lived Experience of the Adult | Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Partnership Board (safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk)

The Six Key Principles of Making Safeguarding Personal

There are six principles of MSP that underpin all of our adult at risk safeguarding work and these are:

| Empowerment | People being supported and encouraged to make their own decisions and informed consent. | “I am asked what I want as the outcomes from the safeguarding process and these directly inform what happens.” |

| Prevention | It is better to take action before harm occurs. | “I receive clear and simple information about what abuse is, how to recognise the signs and what I can do to seek help.” |

| Proportionality | The least intrusive response appropriate to the risk presented. | “I am sure that the professionals will work in my interest, as I see them and they will only get involved as much as needed.” |

| Protection | Support and representation for those in greatest need. | “I get help and support to report abuse and neglect. I get help so that I am able to take part in the safeguarding process to the extent to which I want.” |

| Partnership | Local solutions through services working with their communities. Communities have a part to play in preventing, detecting and reporting neglect and abuse. | “I know that staff treat any personal and sensitive information in confidence, only sharing what is helpful and necessary. I am confident that professionals will work together and with me to get the best result for me.” |

| Accountability | Accountability and transparency in delivering safeguarding. | “I understand the role of everyone involved in my life and so do they.” |

Source: Department of Health Care and support statutory guidance

Information Sharing

Information gathering and sharing is key to the assessment, identification and management of risk. The use and sharing of information will respect confidentiality and the principles outlined in the Data Protection Act 2018 and Caldicott guidelines and will be proportionate to the level of risk to be managed and to the circumstances of the individual. https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/uk-caldicott-guardian-council

The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Information Sharing protocol can be found at https://www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk/council/data-protection-and-foi/information-and-data-sharing/information-sharing-framework

Remember that copies of risk management plans and where necessary copies of the minutes of MARM meetings will be shared and given to the individual/carer.

References (detail of the legislation and the guidance informing content)

- Peterborough and Cambridgeshire Safeguarding Adults Multi-Agency Procedures and Guidance

- Human Rights Act 1998

- The Care Act 2014

- Data Protection Act 1998 (General Data Protection Regulations 2018)

- The Mental Capacity Act 2005

Section Two – Process

Before making a referral for a MARM

- Have you contacted your nominated safeguarding lead (every agency should have a safeguarding lead) or in ASC MASH team colleagues to have a discussion with them?

- Have other areas of support been considered such as signposting to supportive agencies and services?

- Have all other avenues for support and engagement with the adult at risk been exhausted?

- Has a Multidisciplinary Teams Meeting (MDT) already taken place or been considered?

- Is the risk significantly high enough to warrant a MARM?

MARM Checklist

- Does the person have care and support needs as defined by the care act (unable to meet two or more of the outcomes – due to their impairment and not caused by other factors such as homelessness/lack of access to facilities); AND

- From the information available is it believed that the person has capacity to make decisions in relation to their own care and support needs; AND

- Is there evidence that the person is not engaging with a range of professionals, and this has been over a period of time; AND

- Is there evidence of self-neglect which is so severe that it is felt that without a change it will have a devastating effect on the person’s wellbeing which may lead to a permanent change in the persons functioning, and /or may lead to death.; OR

- Is there evidence of the person engaging in risky activity which could have a severe detrimental effect on their wellbeing? (this could include choosing to remain in a domestic abuse situation, associating with known offenders, drug users/dealers, cuckooing being a risk)

If criteria 1-3 are met and either one of 4- 5 then a referral for MARM consideration would be appropriate.

Step 1 – Raising a concern

Where an adult meets the criteria for this guidance, this should initially be discussed with a safeguarding lead or the MASH team if you work in ASC and the practitioner initiating the MARM process should and raise a safeguarding referral to the applicable Adult Social Care (ASC) service via the local Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH) in order that progression of the MARM process be confirmed. Please note that whilst any person can raise a MARM concern, the oversight and lead of these remains the responsibility of the relevant local authority as this safeguarding is a statutory responsibility that sits with local authorities. If there is a professional disagreement about whether or not an individual meets the criteria for a MARM then the referrer and the MASH manager should hold a discussion to ensure that there is consensus and clarification about the arrangements going forward. When making the referral to the MASH the referrer should explicitly state that they want the person to be considered for a MARM. To support the MARM referral to the MASH all possible evidence should be included, and explicit reference made to any unwise decision(s) made by the Adult at Risk. In terms of making safeguarding personal the referrer should advise the Adult at Risk of the MARM referral and what the safeguarding process entails.

Step 2 – Information Gathering

The Adult MASH will receive the referral and will go through the usual process of information gathering to understand and decide the next steps and if applicable, allocate it to an appropriate ASC team to take forward.

Step 3 – Scoping the Risk Action Planning Meeting

A lead ASC Social Worker will be allocated to coordinate the process. The key agencies who are required to be (or become) involved in the Risk Action Planning Meeting will be identified. ASC will lead and coordinate the MARM process; the Chair of the Risk Action Planning Meeting will be an ASC Team Manager or more senior representative.

Depending on the urgency of the case, it may be necessary for professionals to prioritise the MARM Risk Action Planning Meeting. Invitees will be determined on a “case by case” basis but would ordinarily involve representatives from all key agencies who are or should be linked to the case; this may include the Police as they may hold relevant intelligence, and other agencies such as, for example, health professionals, the Fire & Rescue or Housing services. It is a requirement that those key agencies identified must attend the MARM Risk Action Planning Meeting.

When scoping invitees, consider who might be the best person to engage with the individual and work effectively with them – this person may be from one of the key agencies, for example, an outreach worker from a voluntary agency.

Attendees should be of a senior level within their organisations in order to make decisions and deploy resources due to the risks involved within MARM cases

The adult at risk should be invited to attend the MARM Risk Action Planning Meeting, with an advocate or interpreter as appropriate. Where applicable, family members and/or other representatives directly involved with the adult could also be invited to attend or to submit relevant information in advance if they are unable to attend.

The Local Authority Principal Social Workers are available for advice and guidance at any stage.

“There is strong professional commitment to autonomy in decision making and to the importance of supporting the individual’s right to choose their own way of life, although other value positions, such as the promotion of dignity, or a duty of care, are sometimes also advanced as a rationale for interventions that are not explicitly sought by the individual”

SCIE Report 46 (2001).

Step 4 – Risk Action Planning Meeting

The MARM Risk Action Planning Meeting will be chaired by an ASC Team Manager or more senior representative.

If the adult at risk concerned has the mental capacity to understand the consequences of refusing or disengaging from services, participants of the Risk Action Planning Meeting, should follow the framework factors given below in developing a MARM Risk Action Plan:

- Confirm the coordinating ASC Social Worker and who will be the key contact with the adult concerned (these may not be the same person in both roles).

- If a mental capacity assessment has been completed record the date and time and by whom the mental capacity assessment was carried out. Where the information suggests the person’s capacity may have changed consideration of how to evidence capacity should be given and recorded.

- If it is deemed that an adult at risk is making unwise decisions, consider how many times unwise decisions have been made and when this stops becoming an unwise decision and is a danger to life

- Document evidenced based risk factors of significant harm and threat to life.

- Document the adult at risk’s level of involvement and, where known, their desired outcomes. Record, in their words, what the adult at risk is saying

- Record what needs to change to support safety and reduce risk.

- Consider and record all options for supporting engagement with the adult.

- Ensure all applicable agencies are involved, these could include, General Practitioner (GP), Children’s Services, Fire & Rescue, Housing, Shelter, Drug & Alcohol Services, Domestic Abuse Support, Outreach Services (NB: this is NOT an exhaustive list)

- Professionals should identify the support that carers, family members, children or other adults at risk might need, and consider who is best placed to engage and support them.

- Develop a MARM Risk Action Plan with clear actions, timescales and responsibilities

- Document contingency planning arrangements to be instigated if the MARM Risk Action Plan is unsuccessful.

- Set clear review dates and timescales.

- Ensure notes from the meeting are accurately recorded and circulated to all participants and relevant others within 10 working days of the meeting.

Where possible, the adult’s views and wishes/desired outcomes should be included and if they are not present detailed reasons for this should be recorded.

Consider who is best placed to engage with the adult

The MARM Risk Action Plan should consider if the adult would/may respond better to a health, social care, voluntary agency professional, or another person.

Step 5 – Test of Engagement

Once established, the MARM Risk Action Plan should be shared with the individual by the person or agency most likely to succeed (identified at the MARM Risk Action Planning Meeting – see Section 4 above).

Step 6 – Review

If the individual does not engage with the plan, the MARM Risk Action Planning Meeting should reconvene to discuss and review the MARM Risk Action Plan. The case should not be closed because the adult is failing to engage with or accept the plan.

Appropriate advice must be taken as to a reasonable review plan, including consideration of the timescales to be applied (for example from a Line Manager/Head of Service/Legal Services).

At each meeting consideration between agencies should be given as to whether the MARM process has reached its potential, for example would an MDT now equally meet the need?

Step 7 – Case Closure

When working with an adult under the MARM guidance, there must be agreement by all professionals involved in the case that this process is no longer required before it is closed. It should be understood by all agencies that a case under the MARM may be open for a very long period of time.

The main reasons for closure would be:

- The adult is now engaging with professionals to reduce the risks

- The risk is reduced to a level that there is no potential risk of significant harm or death

- The adult is deceased

If by undertaking the MARM this has significant negative outcomes for the adult at risk, consideration should be given to withdraw the MARM process

Timescales

It is important to agree timescales for each part of the MARM Risk Action Planning process to prevent drift. This will be different for each case dependent on individual circumstances.

It is also important to ensure that any decisions made are accurately recorded.

Within the MARM Risk Action Plan, it should be clear what the agreed actions are, who is responsible for carrying out the actions and the timescales involved. Disagreements and any actions taken should also be clearly documented.

Escalation of Concerns

It is every professional’s responsibility to ‘problem-solve’. The aim must be to resolve a professional disagreement at the earliest possible stage as swiftly as possible, always keeping in mind that the adult at risks safety and welfare is the paramount consideration.

The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Adults Partnership Board is clear that there must be respectful challenge whenever a professional or agency has a concern about the action or inaction of another.

The Chair of the MARM Risk Action Planning Meeting holds responsibility for the escalation of concerns as required.

It is recognised that at times there will be disagreements over the handling of concerns. These disagreements typically occur when:

- The adult is not considered to meet eligibility criteria for assessment or services.

- There is disagreement as to whether safeguarding adults’ procedures should be invoked.

- There is dispute about the adult’s mental capacity to make specific decisions about managing risks.

- The adult is deemed to have mental capacity to make specific decisions and is considered to be making unwise decisions.

- Professionals’ place different interpretations on the need for single/joint agency responses.

- Professionals feel that meeting the needs of the adult sits outside of their work remit.

- Resources are not appropriately available or allocated, it must be noted that at all times actions are required to be taken within the law and to not be constrained due to perceived limitations to organisational boundaries.

It is expected that the Safeguarding Adult Partnership Board escalation and resolution process should be used first, however if at any stage it is felt necessary to make a formal complaint, each agency should follow the recognised complaints procedure and adhere to the timescales specified. The Resolving Professional Differences policy can be found at:

Appendix A – Case Scenarios

Case Scenarios Where the MARM Process Would Apply

Scenario One

Tom was a 76-year man living in a council rented bungalow. Tom had a medical history of polyuria, renal failure, acute kidney injury, hyperkalaemia, urine retention, chronic kidney disease and hypertension. There had been numerous referrals into Adult Social Care previously expressing concern about Tom’s ability to care for himself, and concerns about Judith, an adult who was living with him at the time. Tom had always refused any Social Care involvement and support, and it was felt he had capacity to do so. Tom did have a catheter which was routinely changed by District Nurses.

A new referral was received from Tom’s bank, whom he visited every week to withdraw cash. They had concerns, that Tom was looking physically weaker/frailer and were worried that he may be being financially abused by Judith. This was passed to the Locality Team to investigate, initially under a Section 42 enquiry.

Housing was involved as Tom was in rent arrears, and they were considering eviction/court action. They too had concerns around Tom’s ability to care for himself, and concerns around Judith’s role and intentions with Tom. Tom was not engaging with Housing.

Social Care visited Tom, who refused to engage. Tom did not let the allocated worker in his property, although commented he felt unwell before shutting the door. Social Care shared Tom’s comments about feeling unwell with his GP, who decided they would attempt a home visit. This was unsuccessful as Tom did not open the door. Social Care attempted to visit again, and it appeared Tom may have moved items in front of his front door to prevent access.

Social Care decided to request a Police Welfare check. Police attended and Tom disclosed that Judith had been physically abusing him, and she was removed from the property. The Police requested ambulance support, who attended. Tom refused hospital admission. The ambulance crew reported based on their medical expertise/profession that Tom was at risk of death within a few weeks if the situation continued, and that he was at risk of malnourishment.

The case was escalated to MARM. Social Care visited Tom and provided food and drinks, as there was none in the property. Tom did accept this.

The MARM was attended by Social Care, Housing, Mental Health, Fire Service, Continence Service, GP and the Police.

A plan was devised, it was decided given the imminent risk to health/life that the GP and Nurses were the best placed professionals to attempt to engage with Tom. They visited and offered medical examination and hospital admission. Tom did accept this.

As an alternative plan if Tom did not accept support, professionals involved at the MARM offered to provide support / attempt to engage with Tom in ways in which they usually would not. For example, the Nurses agreed to increase their visits, and Housing and Fire Service offered their services to complete “check/welfare” visits if needed.

Scenario Two

Brenda is a 38-year old woman who suffers from multiple sclerosis, has learning difficulties and uses recreational drugs. Brenda’s two children were taken into care as Brenda was unable to keep them safe from harm. The Police were aware that Brenda had been ‘cuckooed’ and was being groomed and exploited by drug users and was possibly being coerced into sex work. Brenda had a number of professionals working with her care and support needs to try to get her to understand how she was being used and abused. Brenda was at serious risk of harm from being involved in risky abusive behaviours and activities that were impacting on her health and wellbeing. Her multiple sclerosis was deteriorating, and she was struggling to keep up her mobility and was at risk of losing her tenancy agreement. Brenda’s learning disability worker, support worker, multiple sclerosis nurse, the police and housing officer all tried to work with Brenda. However, Brenda refused to listen to them and stopped engaging with any of the professionals who were trying to support her.

A referral for a MARM was made to the MASH by Brenda’s multiple sclerosis nurse and a MARM meeting set up and chaired by the learning disability lead. Brenda was invited to the meeting but chose not to attend. All the agencies involved in working closely with Brenda were invited to the meeting and an action plan was agreed. The group made a referral to the local substance misuse agency and the housing association moved her out of her current home, in a bid to move her away from the perpetrators of abuse. Unfortunately, the perpetrators started to meet Brenda in her new home and at another MARM meeting, it was decided that Brenda was to be moved again a little further out of the area.

The MARM panel also agreed to meet with Brenda’s boyfriend to try to engage both he and Brenda to support her care and support needs. Unfortunately, he and the following boyfriend died due to drug overdoses. However, her current boyfriend is proactively trying to help Brenda. He has made sure that Brenda is eating properly and cooks all her meals. Both Brenda and her boyfriend have started to engage with the workers to work with them on the MARM’s identified areas of concern.

Brenda is working well with her support and care workers and the concerns about being cuckooed and being coerced into risky behaviours has subsided. Her boyfriend is also maintaining contact and is supporting Brenda and the case is soon to be closed at the MARM.

Case Scenarios Where the MARM Process Would NOT Apply

Scenario Three

Ben is part of the travelling community living locally and is diagnosed as having type 1 diabetes and self-administers insulin injections twice a day. Recently he has attended the GP surgery explaining that he feels dizzy and is shaking so much that he can’t do his job.

On further discussion Ben admits that he hasn’t been eating a lot and has not taken his insulin for a while, but he can’t remember how long. He tells the GP that he can’t be bothered to take his insulin anymore as the dosage keeps changing up and down and he doesn’t know where he is with taking it. The GP makes an urgent safeguarding referral to the MASH for a MARM as Ben is refusing to take his insulin and by not doing so could die.

The MASH has a discussion with the GP to explain that even though Ben is refusing to take his insulin he is not an adult at risk as he does not have care and support needs. The MASH also explains that Ben has a good relationship with the GP and is engaging with the GP surgery. Other areas of possible support for Ben are discussed.

Ben is currently supported at the GP surgery and is attending regular diabetes appointments with the diabetic nurse. He reports to now understanding why taking his insulin is so important and that he is trying to manage his diabetes with the support of the nurse and by taking his insulin, and eating ‘good foods at proper meal times.’

Scenario Four

Benas is aged 45 years old and is from Lithuania. He is a homeless man with no recourse to public funds (NRPF) and has a leg injury. He sustained the injury when he worked, and this resulted in him having to leave his job. His leg is still very painful, and he has a plaster cast on his leg to support the leg to heal. Benas spends much of his time sitting and standing outside the local supermarket begging for money so that he can buy alcohol. Benas has a local NRPF outreach worker, working with him trying to get him to stay in suitable accommodation and to address his alcohol misuse.

A member of the public saw Benas lying outside of the supermarket with maggots coming out of the sides of his plaster cast. A referral was made to the outreach worker to go and see Benas. Once the outreach worker arrived at the store, Benas ran away into the town.

The outreach worker contacted Banas’s General Practitioner (GP) to report the concerns in relation to Benas and the deteriorating condition of his leg. The GP explained that he felt that if Benas needed medical help, that he was more than capable of either coming to the GP surgery or could go to the hospital.

The outreach worker made a safeguarding referral to the MASH (Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub) requesting a MARM on the basis that Benas was at significant risk from self-neglect and was disengaged from any the agencies who were working with him. The MASH discussed the referral with the outreach worker to explain that Benas had no care and support needs and as such was not deemed as an adult at risk. Benas was choosing to not seek medical help and it was his decision to do so.

The outreach worker continued to see Benas and to engage with him. At the time of the pandemic Benas agreed to go into accommodation during the cold winter months. The outreach worker reported that Benas was eating well and continuing to live in his accommodation and his leg was healing. A referral had also been made to the alcohol and substance misuse service who were starting to engage with Benas. However, Benas still refused to do some proactive things to support his wellbeing such as keeping himself clean and having a shower.

Appendix C – Multi-Agency Risk Action Plan Template

Footnote

[1] The ‘Capacity Guide’ part of the Mental Health & Justice research initiative.

Relevant information for different categories of decision (39 Essex Chambers)

What Makes a Good Assessment of Capacity? | BPS

The situation seems risky to me – Capacity guide

[2] 39 Essex Chambers | Mental Capacity Guidance Note – Inherent Jurisdiction – 39 Essex Chambers | Barristers’ Chambers