Table of Contents

Child Sexual Abuse Strategy

1. Introduction

Cambridgeshire & Peterborough Safeguarding Children’s Partnership (CPSCP) recognises that Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) is prevalent in the UK and that for many victims, the impact of this abuse can be devastating and endure into adulthood. The adverse consequences of CSA can include acute feelings of betrayal, powerlessness, stigmatisation, guilt and traumatic sexualisation, as well as difficulties forming and maintaining relationships, mental health, related problems resulting from trauma and physical health problems. (Meadows et al, 2011).

This strategy aims to ensure there is a shared understanding of the impact of CSA and how, as a partnership, we work together with children, young people and families at the earliest opportunity to prevent long lasting impact.

This strategy seeks to explain;

- How agencies in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough recognise and respond to “CSA”

- How agencies can work together to reduce the chances of children and young people being sexually abused.

This strategy has been created to help improve the ways in which needs and risks are understood, recognised, and responded to at all stages of the “child’s journey”. It is not a “stand alone” document and should be considered alongside several other strategies, including the CPSCP Effective Support for Children and Families document, Child Exploitation Strategy, Sexual behaviours tool and partner agencies CSA Strategies. Together, these reflect the many different aspects of sexual abuse and priority concerns of organisations and professionals.

2. Partnership priorities

The CPSCP has identified four key CSA priorities.

Priority 1: Strategic commitment across all agencies to understand, prevent and reduce the impact of CSA

- Leaders across the partnership will drive CSA as a key priority and will raise awareness of CSA and its effects.

- Education and training around CSA will be delivered to all agencies working with children, young people, and families. This will include those working primarily with the adults in a family to ensure the child’s lived experience is not overlooked.

- The Partnership will engage with children and families to empower them by ensuring they are involved in public health and education campaigns and supported in meeting their children’s needs.

Priority 2: Improve the capability of the multi-agency workforce to recognise and act on the signs of CSA

- Professionals and practitioners will use the Effective support for children and families document to assist their professional judgements in assessing which level of need a child is at and determining the actions required to meet a child’s identified needs.

- Professionals and practitioners will use a range of tools to support their practice to identify signs of CSA at an early stage.

Priority 3: Improve the effectiveness of assessment, planning and interventions to reduce CSA and respond in a consistent and timely way.

- Leaders across the partnership will ensure that CSA is identified and addressed at an early stage.

- Professionals and practitioners will ensure that young people and families know how to access services at the earliest opportunity, this includes signposting families to appropriate services.

- The Partnership Board will hold statutory partners to account and will challenge the effectiveness of multi-agency working to tackle early CSA at the earliest opportunity.

Priority 4: Evaluate our practice and continually improve its effectiveness so we can reduce the CSA of children and young people.

- Leaders across the partnership will evaluate the quality of practice in relation to CSA: early identification, strength-based approach, and a clear focus on the child’s lived experience to inform decision making

- The partnership’s Quality Assurance and Effectiveness Group will regularly examine data and quality assurance information to enable them to monitor the quality of practice across early help, child in need and child protection interventions.

- The Partnership Board will ensure that practitioners and their managers have access to training on the recognition and management of parental non-compliance and disguised compliance.

3. Progressing the priorities

Governance is provided by the CPSCP and scrutiny of progress against the strategic aims and objectives and performance management indicators will be undertaken through the CPSCP Quality and Effectiveness Subgroup.

All Board members are responsible for implementing and embedding this strategy within their own agency and the CPSCP will hold members to account over this.

The impact of the strategy will be assessed using a range of quantitative and qualitative measures. Some of the performance indicators that will be used to measure impact will include:

- A reduction in the number of re-referrals to Children’s Social Care, where CSA is a concern

- A reduction in the number of children subject to child protection plans under the category for CSA for a second time or more over a 12-month period

Audit activity will evaluate the quality of the partnership response to CSA including the child’s lived experience. The relaunch of the CSA strategy will be owned, implemented, and supported by an action plan drawn up by the CSA workstream group.

The partnership will utilise the Centre of Expertise on CSA Data Improvement tool to gather partnership data https://www.csacentre.org.uk/research-resources/research-evidence/scale-nature-of-abuse/

4. Principles

To ensure that CSA is addressed consistently and effectively, all agencies interventions whether early help or statutory intervention should work to the following principles:

- The child is at the heart of what we do. This means that we need to listen / observe the child’s views and experience to understand the impact child sexual abuse has had and is still having on their lives.

- All professionals have a responsibility to identify needs and concerns in relation to children and take action to ensure those needs and concerns are addressed at the appropriate level of intervention. This should always be at the lowest possible level to address the issues.

- Interventions will be conducted openly and honestly with children and families and all agencies will work in partnership with children, parents and carers.

- Assessments will be holistic, taking account of all views including parents that do not live with their children. Assessments will be evidence based and identify strengths as well as areas of concern. Assessments will focus explicitly on each child in the family.

- Plans will be clear and directly related to the strengths and concerns identified in the assessment. All plans will have clear timescales that will be reviewed regularly.

- All agencies will work together positively to address the identified needs and risks for the child and their family. Any concerns about the effectiveness of the interventions with the child should be raised using the ‘resolving professional differences policy’

5. Agency Responsibilities

No one agency can address the complex elements of CSA on its own. Effective interventions, whether targeted support, child in need or child protection depend on professionals developing working relationships based on trust. This includes ensuring concerns are escalated appropriately.https://www.safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk/children-board/professionals/procedures/escalation_policy/

All agencies represented on the CPSCP have a responsibility to contribute to the safeguarding of children across Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. Roles and responsibilities are clearly defined in both statutory guidance and the CPSCP Procedures and include the following:

- To view the safety and wellbeing of children as paramount.

- To ensure that achieving the best outcomes for the child is the primary focus when working with CSA.

- To ensure that their workforce understand the significance of all types of CSA on children and equip their workforce to work effectively in situations where CSA is a feature.

- To share relevant information and collaborate with other agencies and work together to ensure accurate assessments and the early identification of needs.

- To harness and develop resources to ensure that interventions are proportionate, effective, and delivered sufficiently early to reduce the risk of harm.

6. Responsibility to share information

Information sharing is essential to safeguard children, it is imperative practitioners can confidently share information as part of their day-to-day practice.

It is important to remember there can be significant consequences to not sharing information as there can be to sharing information. Practitioners must use professional judgement to decide whether to share, and what information is appropriate to share.

Data protection law reinforces common sense rules of information handling. It is there to ensure personal information is managed in a sensible way. It helps agencies and organisations to strike a balance between the many benefits of public organisations sharing information and maintaining and strengthening safeguards and privacy of the individual.

It also helps agencies and organisations to balance the need to preserve a trusted relationship between practitioner and child and their family with the need to share information to benefit and improve the life chances of the child.

7. Definition of Child Sexual Abuse

To be able to define, recognise and address CSA, it is important there is an agreed shared understanding, across the partnership, of what constitutes CSA.

Whilst it is recognised that there are many definitions of CSA, for the purpose of this strategy, CSA is defined in accordance with the definition contained in Working Together to Safeguard Children (2018):

“Sexual abuse involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening.

The activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example, rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside of clothing.

They may also include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual images, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse Sexual abuse can take place online, and technology can be used to facilitate offline abuse.

Sexual abuse is not solely perpetrated by adult males. Women can also commit acts of sexual abuse, as can other children.”

The term CSA covers a number of areas, this includes both intra familial (sexual abuse that occurs within a family, including sibling abuse) and extra familial sexual abuse (sexual abuse that occurs outside the family). The following boxes highlights some of these areas but is not exhaustive.

CHILD SEXUAL EXPLOITATION (CSE)CSE is a form of CSA. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity

The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology. It can involve children and young people of all ages and genders from all social and ethnic backgrounds. | HARMFUL SEXUAL BEHAVIOURHarmful Sexual Behaviour (HSB) has been defined as sexual behaviours displayed by children and young people, which are considered developmentally inappropriate, and may be harmful towards self or others and/or be abusive towards another child, young person or adult. Those exhibiting the behaviours, or those the behaviours are aimed at, may be either male or female. HSB can include:

|

FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION (FGM)Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female circumcision or female genital cutting, is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as “all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” The practice is mostly carried out by traditional circumcisers, who often play other central roles in communities, for example, attending childbirths. Procedures are mostly carried out on young girls sometime between infancy and aged 15, and occasionally on adult women. For more information see the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough FGM Practice Guidance policy here: | ONLINE ABUSECSA can happen online and may include:

|

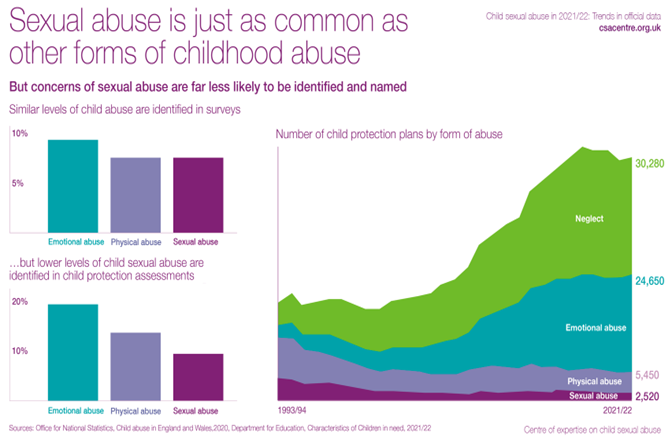

8. National Picture

Locally, across the county we are seeing an increase in the number of children who are the subject of a child protection plan under the category of CSA. This is evidence that as a partnership we are getting better at identifying and responding to CSA in its own right.

9. Why is child sexual abuse difficult to identify?

CSA can be difficult to identify for numerous reasons:

- Children may not recognise they are being sexually abused.

- Children often don’t talk about sexual abuse because they think it is their fault or they have been convinced by their abuser that it is normal or a “special secret”.

- Children may be bribed / threatened by their abuser or told they won’t be believed.

- They may care for their abuser and worry about getting them into trouble.

- Children and young people may be exploring their sexuality and become victims of CSA and are unsure about how to disclose.

Often children do not disclose they are being abused . Reasons for not disclosing include:

- Having no one to turn to.

- Not understanding they were being abused.

- Being ashamed or embarrassed.

- Being afraid of the consequences of speaking out.

- Abuse is historical and they think they have left if too late to tell people.

- Confusion around sexual identity.

When children and young people do disclose, they do so for a variety of reasons including:

- Not being able to cope with the abuse any longer.

- Abuse getting worse.

- Wanting to protect others from abuse.

- Seeking justice.

There are also a number of professional barriers to recognising and responding to signs of CSA including:

- Lack of confidence and not knowing what to do with concerns.

- Lack of education and knowledge of signs of CSA.

- Fear of getting it wrong.

- Organisational pressures including lack of time and capacity to be professional curious.

- Personal experience of abuse and trauma.

- Prioritising parent-professional or therapeutic relationship over reporting concerns.

I didn't know I was sexually abused until I found out what it was

young person

10. Identifying child sexual abuse:

Potential signs and indicators of sexual abuse in children, young people and their families

Research indicates that just one in three children who have been sexually abused by an adult told anyone. For those abused by another child this was even less, with five out of six not speaking to anyone (Centre for expertise on CSA, 2023)

It can be difficult for professionals to identify with certainty, that a child or young person is the victim of CSA. A child may show no signs at all that they are being sexually abused, or they may show some signs. Often signs can be similar to signs and indicators of other child experiences. However, it is important that professionals are vigilant and ensure that they are professionally curious, if they suspect a child may be the victim of CSA.

The table on the following page shows some of the most common potential signs of CSA. Please note, the signs and indicators are not exhaustive.

| Emotional | Behavioural | Physical | Abusive Behaviour | Family Vulnerabilities |

|

|

|

|

|

11. Lived experience of children and young people

There are numerous reasons for children not disclosing abuse, these include fear of the abuser, fear of the consequences, fear of not being believed, and fear of loss of control.

Children are more likely to disclose abuse to adults who they trust and have a relationship with. It is important that the adult can listen and take a measured response based on the presenting risk and bearing in mind the reasons why children don’t seek help. However, often the child will not make a disclosure and judgements are based on other lived experience factors.

The lived experience is what a child sees, hears, thinks and experiences on a day-to-day basis that impacts on them emotionally, physically, educationally, developmentally etc.

An important principle is to put yourself in the shoes of the child and think ‘what is life like for the child right now’. Observing the child and their interactions with others is particularly important when children are pre-verbal or when children have speech and language communication needs.

..don't make assumptions about us, our situation and stories - we are more than what you read in our case files, and you can't always believe everything that's in them. You do know some things about us but probably not all, although you sometimes seem to think you do. Our situations can be complex and may be hard for you to understand, so you need to take time to get to know us as individual human beings

14 year old

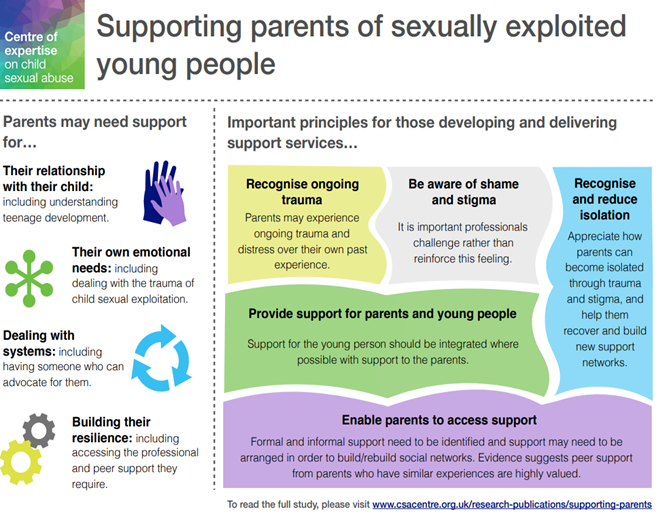

12. How parents seek help

The blocks for parents seeking help are like the reasons why children don’t seek out help. However, when parents do ask for help it appears, many don’t receive it.

The key message for professionals is the need to be proactive in seeking support for families who are struggling. Equally important is the role that fathers/ male carers play in caring for their children. Fathers/ male carers are often excluded from conversations and as a result their role may be ignored or not fully understood within the dynamics of the family’s functioning.

The first impression we get when we meet you is very important. Whether you speak to us clearly and respectfully and whether you show an interest in us and our children as individuals. We would like you to listen to us and talk with us rather than at us. We sometimes feel patronised and made to feel small by professionals, especially if we're young and we didn't have good parents ourselves. Sometimes you make us feel that we can't ever be a good parent. We need encouragement so we don't end up feeling that we'll never move forward

Parent

13. Prevention of CSA

The following resources are available to help talk to children/ young people, families and carers about CSA. Please note that the following information is not exhaustive but is a selection of help and support that is available.

https://www.safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk/children-board/professionals/csa/ – Safeguarding partnerships CSA information and resources.

NSPCC – Underwear rule –

The NSPCC has developed a campaign with 5 easy rules to keep children to stay safe;

- Privates are Private – Your underwear covers up your private parts and no one should ask to see or touch them. Sometimes a doctor, nurse or family members might have to. But they should always explain why and ask you if it’s OK first.

- Always remember your body belongs to you – No one should ever make you do things that make you feel embarrassed or uncomfortable. If someone asks to see or tries to touch you underneath your underwear say ‘NO’ – and tell someone you trust and like to speak to.

- No means No – You always have the right to say ‘no’ – even to a family member or someone you love. You’re in control of your body and the most important thing is how YOU feel. If you want to say ‘No’, it’s your choice.

- Talk about secrets that upset you – There are good secrets and bad secrets. If a secret makes you feel sad or worried, it’s bad – and you should tell an adult you trust about it straight away.

- Speak up, someone can help you – It’s always good to talk about stuff that makes you upset. If you’re worried, go and tell a grown up you trust – like a family member, teacher or one of your friend’s parents. They’ll say well done for speaking out and help make everything OK. You can also call Childline on 0800 1111 and someone will always be there to listen.

The “PANTS” information on the NSPCC website contains useful information for both professionals and parents about how to talk to children about CSA. There are a number of helpful resources available, including resources aimed at children with disabilities. Available are lesson plans, teaching guidance, a PANTS presentation, leaflets and guidance – including the underwear rule in five languages. For further information visit https://www.nspcc.org.uk/preventing-abuse/keeping-children-safe/underwear-rule/

- Managing allegations made against a child – explains how an allegation of abuse may be made against a child, how people who work with children can respond and how to decide if a concern is a child protection issue.

- Protecting children from sexual abuse | NSPCC Learning – Information to help you understand how to recognise indicators and learn how to respond to concerns.

- Sexting: advice for professionals – Advice about sexting and what to do to help a young person who has received or sent an explicit image, video or message.

- Sharing nudes and semi-nudes: advice for education settings working with children and young people – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) – Guidance on responding to incidents and safeguarding children and young people

- Recognising and responding to abuse – What to do if you have concerns that a child know through your work or volunteering has experienced abuse and neglect and how to respond if a child discloses abuse to you.

- https://www.safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk/authoritative-practice/ Information on how to prepare for having difficult conversations with children and young people, gathering lived experience and professional curiosity.

- https://www.csacentre.org.uk/our-research/responding-to-csa/understanding-parents-needs/ – link to a report which highlights the importance of supporting positive relationships which benefit the child, and outlines challenges for supporting parents and mechanisms for being more inclusive. Overall, it gives a sense of parents as a key piece of the puzzle for addressing child sexual exploitation more holistically.

- https://cambridgerapecrisis.org.uk/ – Cambridge Rape Crisis Centre offers free specialist support to women and girls across Cambridgeshire who have been subjected to sexual violence.

14. Assessment

CSA is a damaging form of child abuse. The signs of CSA may not be immediately obvious to the professional and are often part of a complex family picture that can on occasions, be explained away or that simply overwhelm the professional. Some children and young people may be the victims of historical CSA, this may impact on possible signs and indicators that the child/ young person may display.

Protecting children and young people involves professionals in the challenging task of analysing complex information about human behaviour and risk. It is rarely straightforward and responses should be based on robust assessment, sound professional judgement and where appropriate statutory guidance. It is important that assessments include consideration of all of the adults in a child’s family environment.

I. Early help assessment

Protecting children and young people involves professionals in the challenging task of analysing complex information about human behaviour and risk. It is rarely straightforward, and responses should be based on robust assessment, sound professional judgement and where appropriate statutory guidance.

Targeted Support (Early Help)

Working Together 2018 emphasises the importance of local agencies working together to help children who may benefit from early help services. Early help assessments should identify what help the child and family might need to reduce the likelihood of an escalation of needs to the level that will require interventions through a statutory assessment conducted under the Children Act 1989.

Professionals should work within the guidance contained in the Effective Support for Children and Families in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough (Threshold) Document when undertaking an Early Help Assessment.

Where families are identified as having ‘Emerging’ or ‘Complex Needs’, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough promote the completion of an Early Help Assessment in order to identify any support needs required. An Early Help Assessment must be completed at the earliest possible opportunity after the identification of unmet needs and must be a holistic assessment, considering the whole family. Any professional who knows the child/ren can carry out the assessment and must liaise with other professionals who might need to be involved. The professional completing the Early Help Assessment will act as ‘lead professional’ for the family and will conduct an initial Team Around the Family (TAF) meeting to coordinate the support around the family.

This could be a GP, teacher, health visitor – the decision should be made on a case by case basis and be informed by the views of the child and family concerned.

An Early Help Assessment must only be undertaken with the agreement of the child and family and requires honesty about the reasons for completing the assessment as well as clarity about the presenting concerns.

Saying no to early help services does not mean that specialist safeguarding services will become involved, except where there is a risk of significant harm to the person concerned, or where they may present a significant risk to others.

II. Statutory assessment

A referral should be made to Cambridgeshire or Peterborough Children’s Social Care who will consider the need to undertake a statutory assessment. Where an assessment is deemed appropriate, the Social Worker will complete the assessment within 45 working days. For further guidance around thresholds for early help and statutory intervention please refer to the Effective Support for Children and Families in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough (Threshold) Document[1].

15. Role of the Sexual Assault Referral Centre

For any child where CSA is a concern, whether acute or non- acute, a CSA Medical at the SARC should be considered. The process to refer a child or young person to the SARC must have the child or young person’s welfare at the centre. Any such decision is a joint agency decision and a strategy meeting is necessary. The SARC provides a holistic medical examination, providing forensic examinations and / or injury checks and documentation, STI screening for under 13’s, emergency contraception and HIV Pep (over 13’s) as well as onward referrals into other services for ongoing support. A young person can self-refer into the service, however as safeguarding is paramount, a Children’s safeguarding referral will be made for anyone under the age of 18 years.

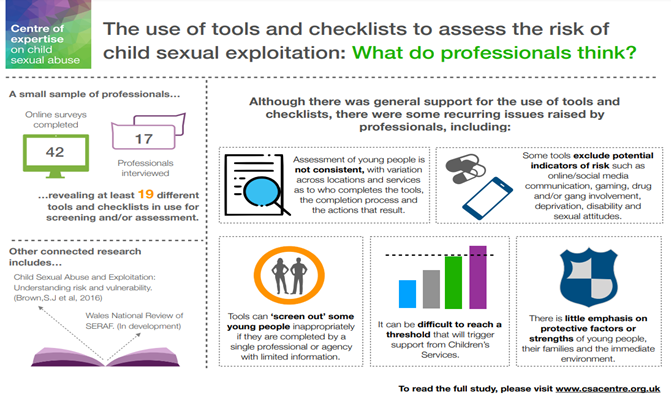

16. Tool to help assess if behaviour is sexually harmful

Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Childs Sexual Behaviours Assessment Tool:

Professionals who work with children and young people often struggle to identify which sexual behaviours are potentially harmful and which represent healthy sexual development.

CPSCP have developed a local Childs Sexual Behaviours Assessment tool to support professionals. The tool can be used to help identify and respond appropriately to sexual behaviours. To ensure a consistent approach to assessing possible sexually harmful behaviour, partnership agencies have agreed that this tool will be used by all practitioners. A link to the tool can be found here.

Child Sexual Behaviour Assessment Tool

The tool uses a system to categorise the sexual behaviours of young people and is designed to help professionals:

- Make decisions about safeguarding children and young people

- Assess and respond appropriately to sexual behaviour in children and young people

- Understand healthy sexual development and distinguish it from harmful behaviour

By categorising sexual behaviours professionals across different agencies can work to the same standardised criteria when making decisions and can protect children and young people with a unified approach.

17. Template for identifying and responding to CSA

Centre of Expertise on CSA – Template for identifying and responding to CSA:

This template has been designed to support professionals across a range of organisations and agencies in systematically observing, recording and communicating their concerns about possible CSA.

It aims to create a common language for professionals to discuss, record and share concerns that a child is being, or has been, sexually abused. It aims to help you:

- consider, identify and clearly record signs which may indicate that CSA is or has been taking place

- discuss and explore concerns that a child is being or has been sexually abused and communicate those concerns to other organisations and agencies.

This is not a diagnostic tool, nor is it intended for use as a ‘risk assessment’ or a ‘box-ticking exercise’: a child may show no signs or many that they are being sexually abused, and the signs they show may indicate sexual abuse or something else that is happening in their lives.

The template is not a substitute for further observation or for directly communicating with children and their families, but it can act as a prompt to help you decide when to talk to children, their parents/carers or other agencies – and what to talk to them about. It should be used to inform, rather than determine, professional decision-making.

Remember that children’s behaviour and emotional responses are different at different ages – what is worrying in a three-year-old may be considered ‘normal’ in a 13-year-old. In interpreting signs and 3 indicators of possible abuse, you will need to use your understanding of child development and your knowledge of the individual child about whom you have concerns.

Further guidance on how to complete the template and a copy of the template is available via this link; https://www.csacentre.org.uk/documents/signs-and-indicators-a-template-for-identifying-and-recording-concerns-of-child-sexual-abuse1/

[1] The CPSCP’s Threshold Document can be found at http://www.safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk/children-board/professionals/procedures/threshold-document/

Version Control ; This strategy runs from December 2023- December 2025. The content will be reviewed on an annual basis.